Western skunk cabbage goes by a much more romantic name in Canada: swamp lantern. Both names carry accurate descriptors depending on which elements of the plant you want to highlight. If you're inclined to judge a plant with your nose, skunk cabbage might be your preferred name. The plant puts off a pungent skunk-like odor to attract the flies and beetles that pollinate it. But if you're a more visually oriented person you might prefer to call it swamp lantern because of the luminous way the bright yellow bracts stand out from the surrounding shade of the forest.

Swamp lantern has some of the largest leaves of any plant in the Pacific Northwest, and they were used by native peoples in a way similar to how we use waxed paper. The huge elliptical green leaves were used to line cooking pits, as mats for berry drying, to wrap food for storage, and were folded for use as plates and cups.

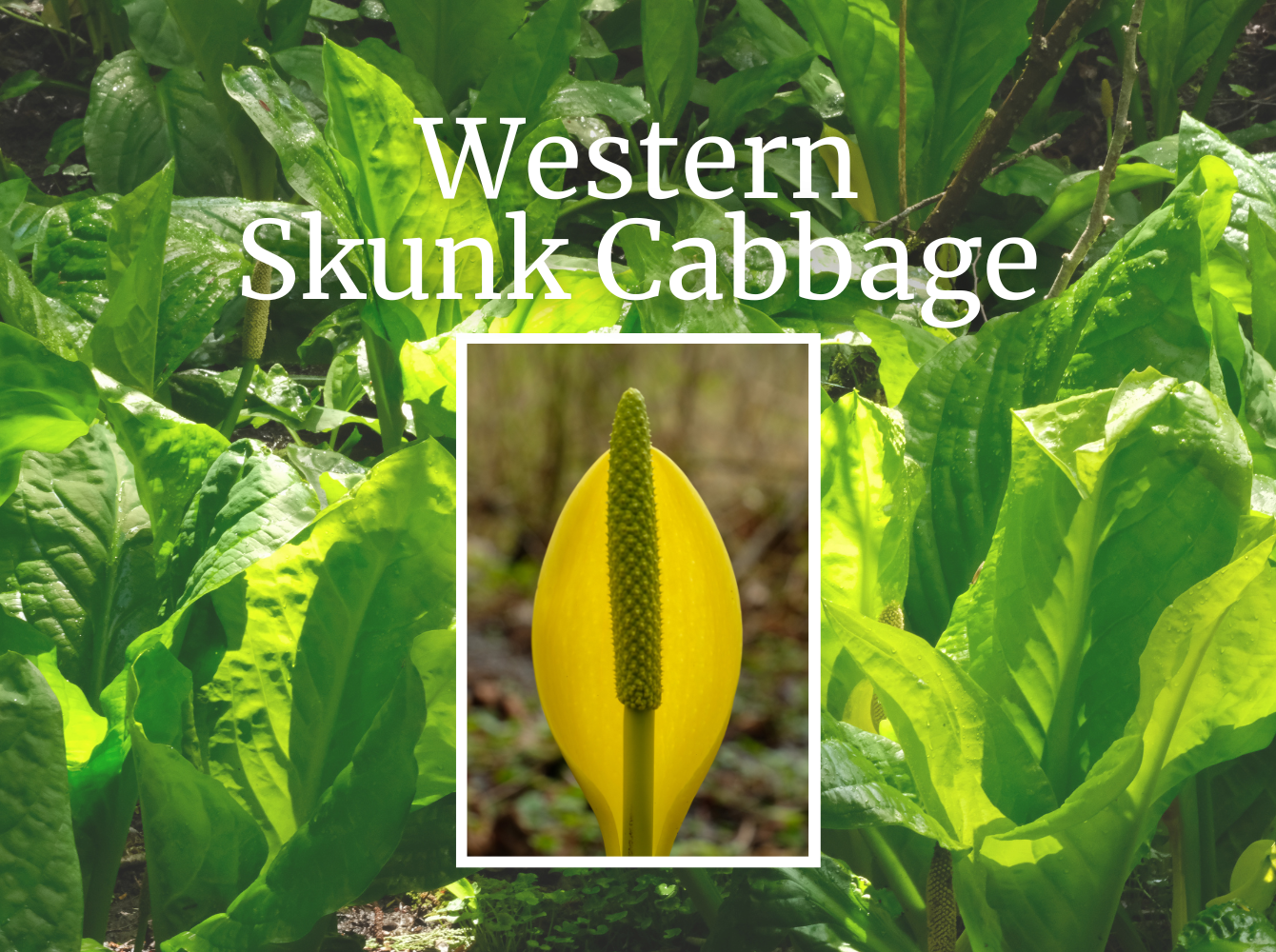

The flowers emerge from March to May, and they form on a spike that is hooded by a bright yellow bract. Bracts are modified leaves, and on skunk cabbage the yellow bract is so dramatic that you might confuse it for a giant petal, but the actual flowers form on a spike underneath the bract. If you are interested in learning even more fancy words, you could refer to the bract and spike as a spathe and spadix. The spathe is a leaf-like curved bract that surrounds the spadix, the flower-bearing spike. I love this myth of the Kathlamet Indians recounted by Erna Gunther in her book "Ethnobotany of Western Washington" that gives a story to the spathe and spadix:

In the ancient days, they say, there were no salmon. The Indians had nothing to eat save roots and leaves. Principal among these was the skunk cabbage. Finally the spring salmon came for the first time. As they passed up the river a person stood upon the shore and shouted: "Here come our relatives whose bodies are full of eggs. If it had not been for me all the people would have starved."

"Who speaks to us?" asked the salmon.

"Your uncle, skunk cabbage," was the reply.

Then the salmon went ashore to see him, and as a reward for having fed the people he was given an elk-skin blanket and a war club, and was set in the rich, soft soil near the river. There he stands to this day wrapped in his elk-skin blanket and holding aloft his war club.

You can find this plant near streams and swamps from Southern Alaska south to central California and also east to Montana and Wyoming. Skunk Cabbage is considered an invasive species in the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, and elsewhere in Europe, having been introduced as an ornamental in large-scale gardens (the smell makes it not-so-suitable for small gardens). The plant propagates by seed and can take 3-6 years before it flowers - it spreads slowly but persistently in swampy areas and can outcompete native European vegetation.

Skunk Cabbage is not particularly valued as a food because it contains large amounts of calcium oxalate, a toxic compound that makes the mouth and digestive tract feel as though hundreds of needles are stabbing it all at once. Not so pleasant. Calcium oxalate can be destroyed through cooking or drying, so the plant - particularly the root which is high in starch - was used as a survival food in spring. Bears and elk are also reported to enjoy eating the root and plow up swamps to get at it.

Though not prized for its culinary attributes, many coastal peoples made use of skunk cabbage for medicinal purposes. The Hoh and Quileute used a decoction of the roots to relieve stomach ailments, and a poultice of the mashed root was used to treat blood poisoning, skin burns, and boils. In "Ethnobotany of the Southern Kwakiutl Indians of BC" an instance was recorded in which pulverized root was rubbed into a child's head to make his hair grow. I don't know if this actually works, but I imagine there's a market for this. Maybe skunk cabbage will appear next on an infomercial for stimulating hair growth, right after a viagra advertisement. The Makah used a poultice of warmed leaves for chest pain, and the Quileute and Skokomish apply them to cuts and swellings. Smoke from burning roots was used to treat influenza, rheumatism, and bad dreams.

As if this stinky plant wasn't already cool enough, listen to this: scientists think this plant might have crossed the Bering Land Bridge during the late Tertiary. There is a closely related plant in Asia, Lysichitum camstchatcensis, located on the other side of the Bering Strait. It's impressive enough that humans made it across, and we have legs. When climatic conditions were favorable Skunk Cabbage slowly worked its way from Asia to North America. What a persistent plant.